Patients who have persistent pain often want to know:

Why has my pain lasted this long (is something wrong?)? and will it ever get better or go away?

In Part 1 of this series (“How to Talk to Patients in Pain”), I tried to provide some ways to answer the common question from patients in physical therapy of:“Can you treat my pain, or do I just have to learn to live with it?” with a discussion of what type of language can be helpful (vs. harmful) and why that is important to consider.

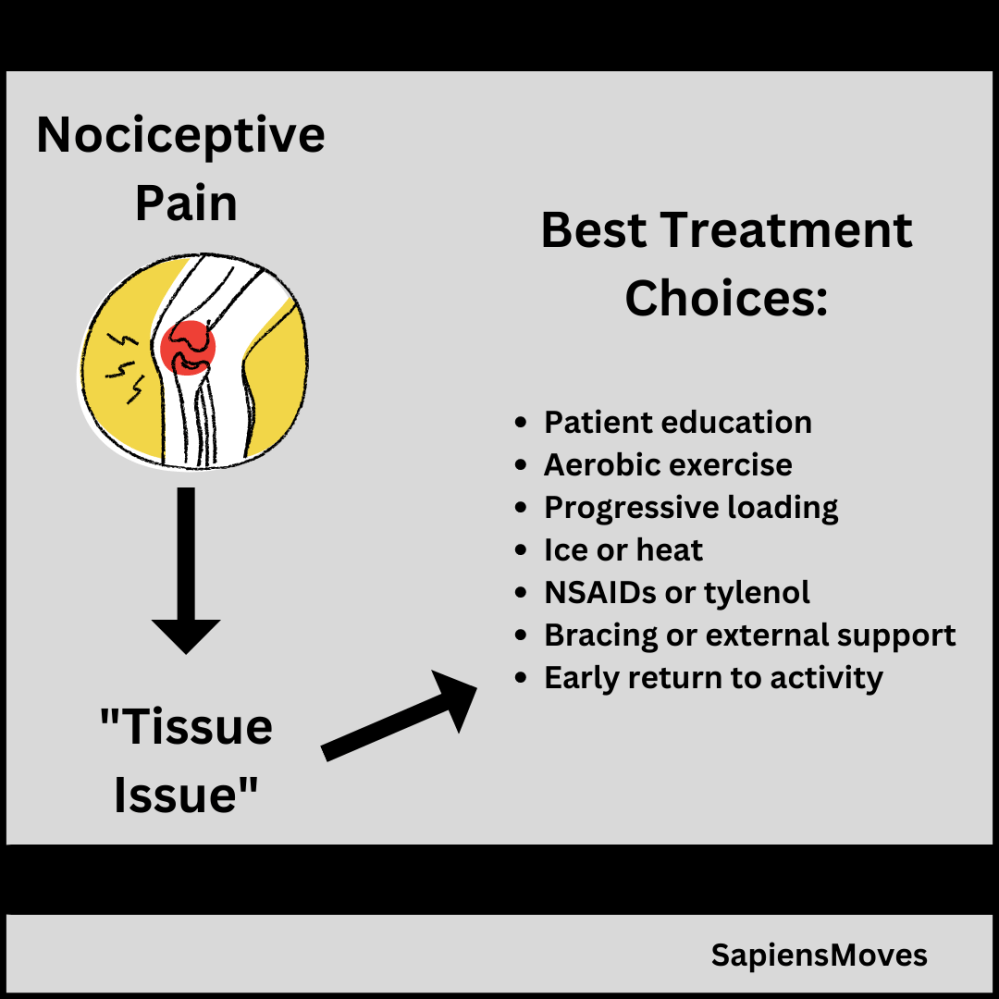

In Part 2 of this series, I introduced the idea of a “Mechanisms-Based Approach” to pain management in physical therapy to try to address another common patient query of: “Why Am I in Pain?” I also gave some potential ideas to the subsequent questions often asked by patients of, “What Can I (and You) Do About It (my pain)?” I started to answer the question of what treatments may be best given a suspected dominant pain mechanism. The choices of treatments for nociceptive driven pain usually match what people commonly expect as options to treat an acute, tissue-based (at least non-nerve tissues!) injury and could include those discussed in that Part 2 Post.

In this post, I’d like to talk more about addressing the question of best treatment options for a (peripheral) neuropathic dominant pain mechanism or a nociplastic pain mechanism.

Treating Peripheral Neuropathic Pain

For a peripheral neuropathic pain mechanism, the main driver of this type of pain is thought to be irritation of a peripheral nerve. This could be a nerve like the sciatic nerve that travels down the back of the leg in the lower body or the median nerve that travels through the arm and hand. Nerve cells are just like other cells in our body in that they need oxygen and nutrition and work best when they are NOT subjected to extremes of mechanical loading (e.g., high tension stretches or lots of compression pressure). For a more in depth look at the health of nerve cells with a mechanical and physiologic perspective, I would highly recommend the approach to treatment called “neurodynamics,” that takes into consideration both mechanical and physiologic health of nerves and the excellent books by Michael Shacklock: Clinical Neurodynamics and David Butler: The Sensitive Nervous System.

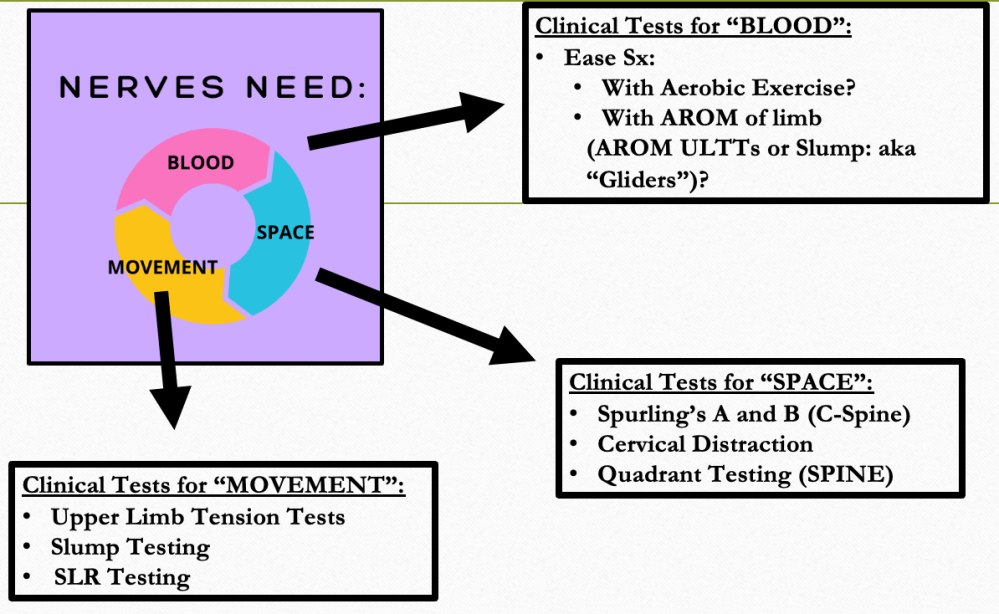

In order to help an injured nerve calm down and heal, it can help to think about nerves responding to: “space, movement, and blood flow”:

If you suspect a peripheral nerve as the primary cause of a patient’s pain presentation, you could test that hypothesis with some clinical tests in these different areas as shown in the figure below:

And, you could match treatment choices to address the suspected cause of irritation or sensitivity at that nerve. Some ideas of potential treatment choices are shown in the figure below:

Treating Nociplastic Pain

If you remember the information that I presented in Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, nociplastic dominant pain is usually indicative of an overly sensitive alarm system or “processing dysfunction,” where the output of pain is not really reflective of the amount of tissue damage of perceived threat of tissue damage and can be triggered with very low inputs (e.g., the touch of clothing). This type of pain is less predictable, and so can be harder to treat, but that does not mean that there are not good treatment choices. Just like the other two dominant mechanisms discussed, we want to match our treatments to the proposed cause. With this dominant mechanism, we want to selecttreatments to try to drive neuroplastic change and make the system less sensitive; we want the alarm system to ramp down and stop going off!

Good treatment options for this type of pain include teaching patients about pain (i.e, pain neuroscience education), graded motor imagery, and sensory retraining.

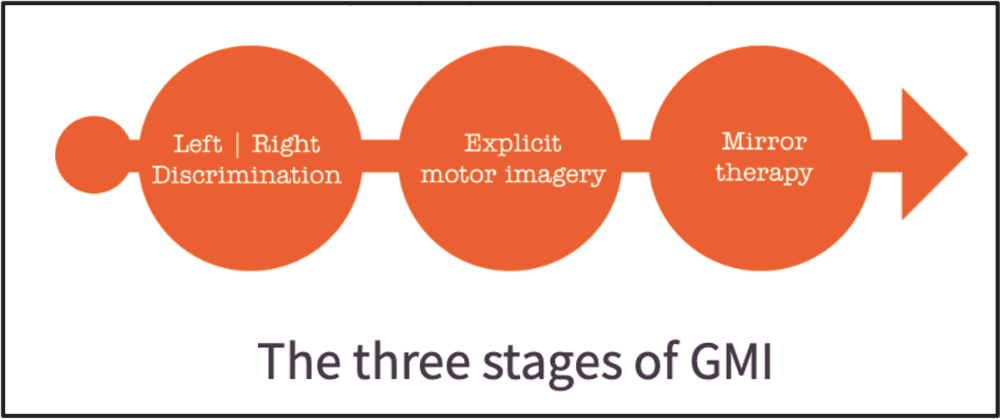

Graded Motor Imagery

Graded Motor Imagery (GMI) is a three-stage progression of treatment that seeks to alter some of the maladaptive neuroplastic changes that we think may be supporting the persistence of this type of pain- such as “smudging” in the sensorimotor cortex (Moseley, 2012). See the figure below for the three-stage process and check out the GMI Website from the NOI group to learn more about this fantastic treatment process:

Sensory Retraining

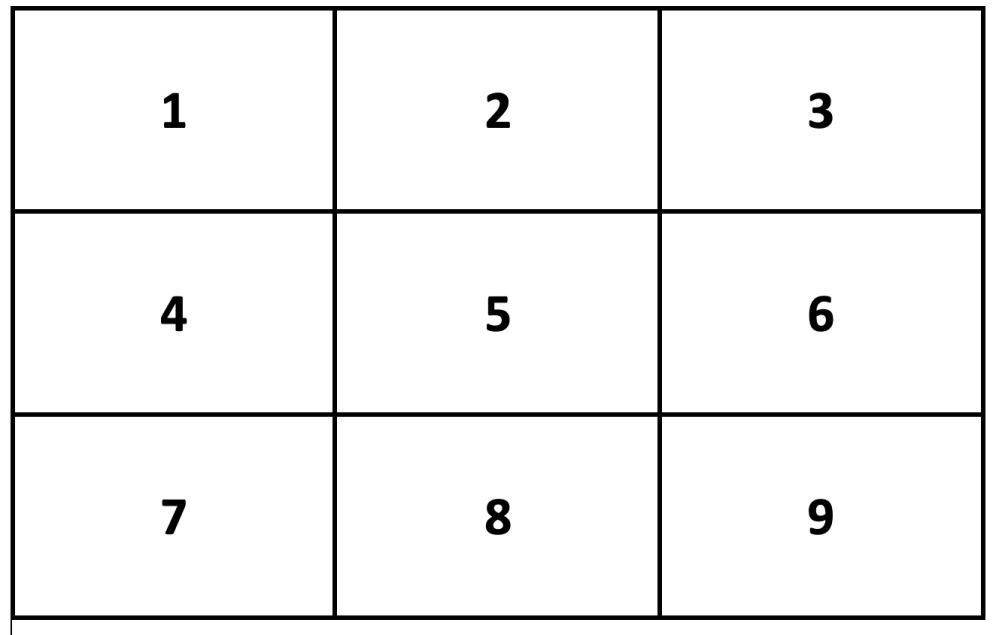

As described prior, individuals with nociplastic type pain may be overly sensitive to light touch from clothing or other objects (i.e., allodynia) and may also have trouble with localizing sensations at the painful body area (Moseley, 2008). Often times these patients will benefit from graded desensitization progressions and can even have symptom improvement if trained on their ability to localize sensory input. I will often do this in clinic with the use of a numbered block grid, like the one shown below and use each numbered box as a separate area that a patient can learn to feel. For example, I could trace an imaginary grid on a patient’s low back and teach them which box corresponds with number 1, 2, 3…then, once they are familiar with the schema, we can try to evaluate if they can feel when a stimulus is applied to each box (i.e., improve their ability to localize stimuli with sensory retraining practice).

Other treatment options that may be helpful for individuals with primarily peripheral neuropathic and nociplastic types of pain could be manual therapy, strength training or aerobic exercise, modalities such as TENS or heat/ice and potentially adjunct treatments such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and possibly medications that are more effective for these types of pain. Some medications that have demonstrated best efficacy for neuropathic and nocplastic pain are those in the following classes of medications: gabapentinoids (e.g., gabapentin), Tricyclic Anti-Depressants (TCAs), and Selective Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) (Attal, 2019; Finerup, 2015; Mathieson, 2020; Moisset, 2020)

A recent study looked at the effectiveness of gabapentinoids for types of neuropathic pain and found that they were pretty effective for some people, about 40% of their sample had up to 50% or greater pain relief, but a high proportion (70%) had at least a minor side effect from the medication, see figure below (Mathieson, 2020).

Also, it is important to ask about and address any lifestyle related factors such as sleep, nutrition, and mental health as emphasized in the biopsychosocial model of care and as described in the seven-factor radar plot diagram of pain mechanisms that talked about in Part 2.

I hope this series of posts has helped shed some light on how we use our best understanding of pain science and integrate that into our approaches to best evaluating and treating pain within physical therapy settings.

References:

- Attal N. Pharmacological treatments of neuropathic pain: The latest recommendations. Revue Neurologique. 2019;175(1-2):46-50. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2018.08.005

- Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14(2):162-173. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70251-0

- Mathieson S, Lin CWC, Underwood M, Eldabe S. Pregabalin and gabapentin for pain. BMJ. Published online April 28, 2020:m1315. doi:10.1136/bmj.m1315

- Moisset X, Bouhassira D, Avez Couturier J, et al. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for neuropathic pain: Systematic review and French recommendations. Revue Neurologique. 2020;176(5):325-352. doi:10.1016/j.neurol.2020.01.361

- Moseley LG. I can’t find it! Distorted body image and tactile dysfunction in patients with chronic back pain: Pain. 2008;140(1):239-243.

- Moseley, G.L., Butler, D.S., Beames, T.B., and Giles, T.J. The graded motor imagery handbook. Adelaide, Australia: NoiGroup Publications; 2012.

2 Comments Add yours