Artists talk about the importance of “Negative Space” to compliment the figures and pictures in effective art pieces. The “white space” or emptiness surrounding objects has been described as the genius that balances and compliments the art images, sound notes (music), or physical presence (sculpture) in order to create the most powerful effect on the audience (Mattens, 2011). I have been seeing more and more the importance of “space” in my line of work as a physical therapist as it relates to training load, recovery, and performance. I would like to add a positive reframe to this narrative and describe the time between training loads as a “Positive Space” because it is so crucial to training and recovery. This “Positive Space,” between training sessions is when muscles, nervous system and other tissues adapt and get STRONGER! Keep reading to find out how to maximize the “Positive Space” in your training and exercise prescription in rehabilitation settings…

3 Ways to Apply the Concept of “Negative Space” to Your Training:

Do Some WORK (i.e., Train Hard)

In order to have space between objects of beauty in art- you must create some art (do some work)! In the physical performance realm, this means that if you want to get stronger, you have to lift some heavy weights! If you want to get faster as a runner, or improve your endurance, you have to go on some hard training runs!

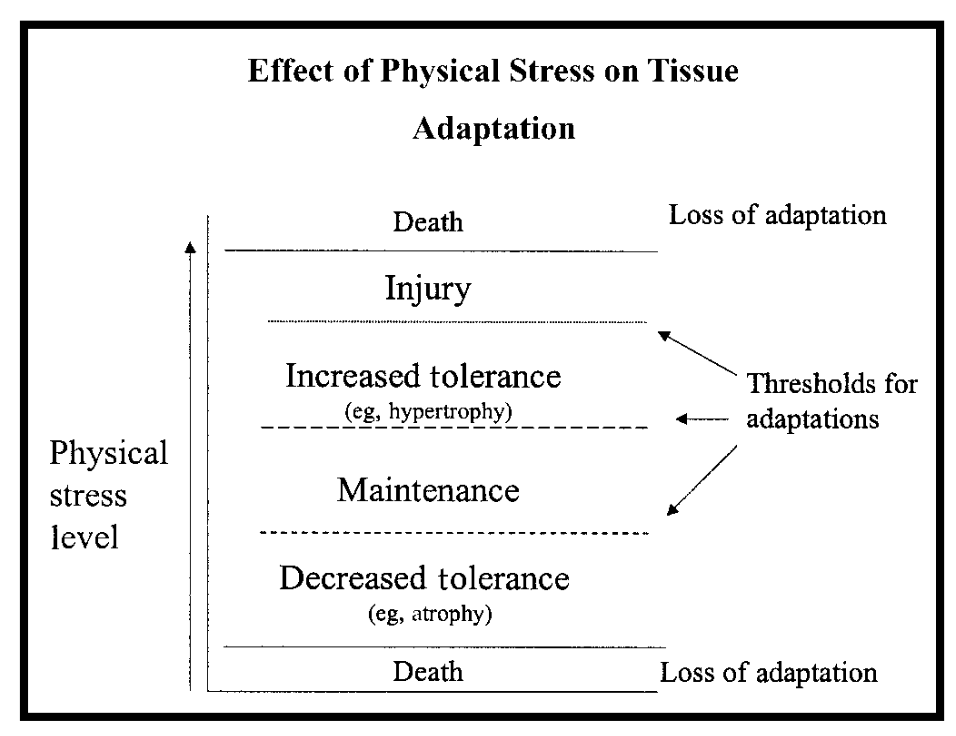

Additionally, you must make that “load” or training session sufficiently challenging (e.g., “intensity” of training) that you induce the changes that you want to see. That means loading with a focus on tissue adaptation. According to “physical stress theory,” tissues respond to the mechanical demand placed on them with predictable adaptations (Mueller, 2002). See figure below from Mueller, 2002:

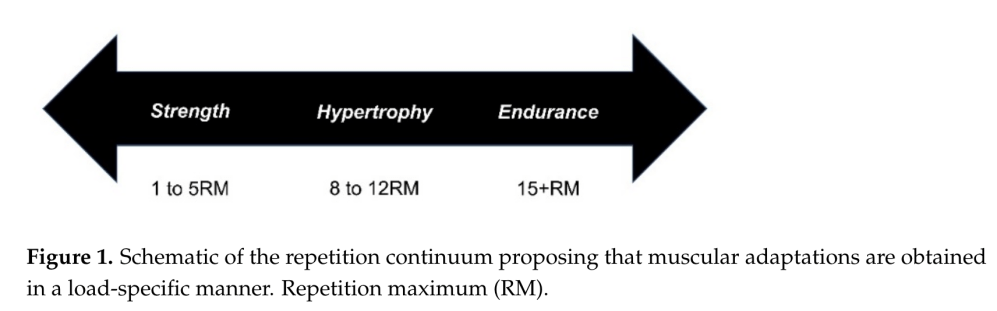

If you want to improve muscle strength, most research emphasizes strength training with weights at least greater than or equal to 60% of your 1 repetition maximum (1 RM) (Brumitt, 2015; Schoenfeld, 2021; Schoenfeld, 2017). Using a percentage of your 1 RM can also help with programming depending on your goals of training (e.g., strength, hypertrophy, or endurance). See figure below from Schoenfeld, 2017.

Finding a “1 rep max” in order to calculate your 60% 1RM threshold does not need to mean performing the heaviest repetition that you can. It can be a proxy measurement, meaning you can estimate your 1RM by using one of the percentage charts linked below. Simply use a moderate weight to perform repetitions until you cannot do anymore (e.g., goal to pick a weight that you cannot do more than 8-12 repetitions); then take a look at this 1RM chart from NSCA (National Strength and Conditioning Association) to calculate what that means for a 1RM (e.g., if you can do 8 repetitions of a squat exercise at 120 lbs, then your estimated 1RM would be 150 lbs).

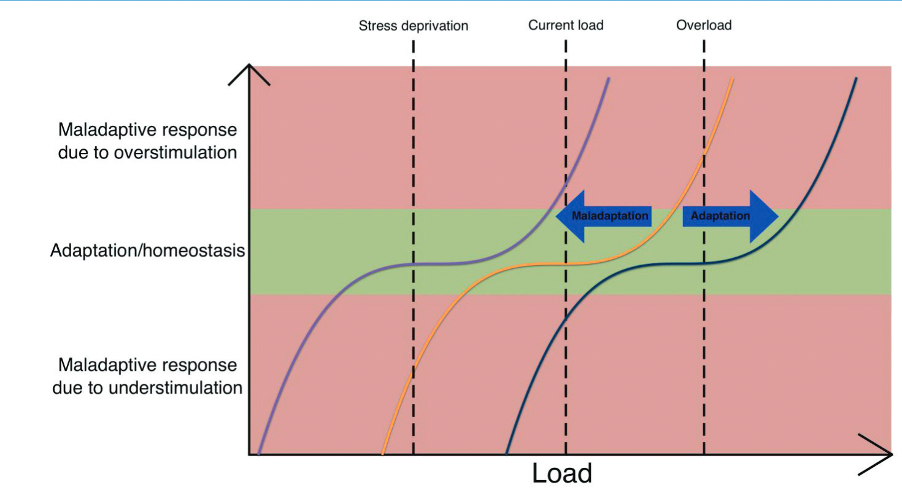

Other body tissues also respond positively to finding the right amount of “load” or exercise stress. For example, tendons placed under moderate loads and given sufficient time to recover can increase their “load tolerance” (see right arrow shift in figure below from Docking, 2019). Also, from the figure below, doing no exercise/loading can create just as detrimental of a response as doing too much! Tendons, like muscle, bone, cartilage need some amount of load to keep homeostasis or what has been termed, “mechanostat point” (Docking, 2019). See Figure Below from Docking, 2019

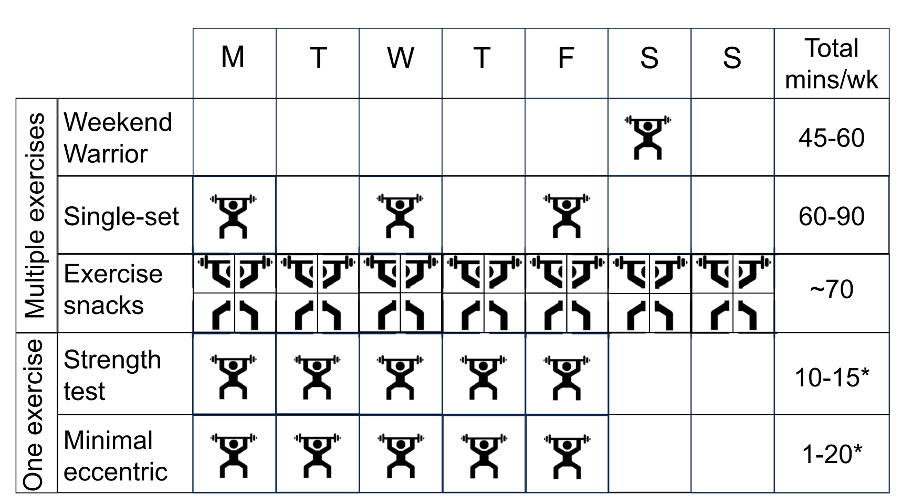

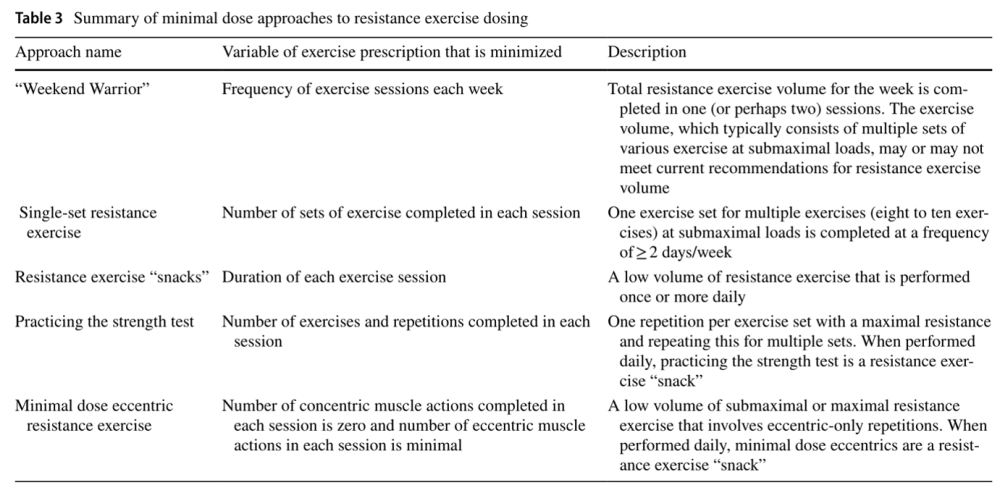

As mentioned above, it is important to DO SOME WORK (e.g., strength train if your goal is improving muscle strength). Interestingly, though, for untrained individuals, you may be able to get away with doing a minimal amount of work and still see increases in strength. For example, a recent review paper looked at the minimum doses to attain improvements in muscle strength and reviewed of five types of “minimal dose” strategies (“weekend warrior”, “single-set”, “exercise snacks”, “strength test”, and “minimal eccentric”). They found that even modest training frequency (in some cases as few as 1 training day per week and as little as 60 minutes per week) could lead to strength gains (Nuzzo, 2024). This is less than what is recommended from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), which recommends a minimum of 2 days per week of strength training targeting all major muscle groups. See Figure and Table below from Nuzzo, 2024 on “Minimal Dose Strategies” for Strength Training:

Part of why I wanted to mention the study above is that the key is to do SOME work! The benefits of strength training are myriad including reducing mortality risk, increasing overall daily movement function, and preserving independence later into life…not to mention the potential for improved athletic performance! For more on the importance of strength for longevity and athletic performance, see my prior post: Making the Case for Stronger Feet and Hands.

Other studies have demonstrated that increasing frequency of training may not lead to greater strength gains if volume and intensity are held constant; In one study with trained individuals, 6 hours of training per week had the same strength and muscle hypertrophy gains whether split into 6 days (1 hour per day) vs. 3 days (2 hours per day) over the course of the week (Colquhoun, 2018).

2. Focus on Optimizing “Positive Space” Between Training Sessions

Your body tissues need recovery period. After a hard strength training session your muscles will experience a period of weakness and without a sufficient time to recover, the adaptation of improving strength will not be there. Furthermore, the type of body tissue (e.g., muscle, tendon, bone, cartilage) and the intensity of your training session or “load” at that tissue will influence how long this recovery period needs to be to see positive adaptations from it. Thus, the “Positive Space” considerations may be very different depending on the type of training you are doing and type of body tissue you are hoping to strengthen, rehabilitate etc.!

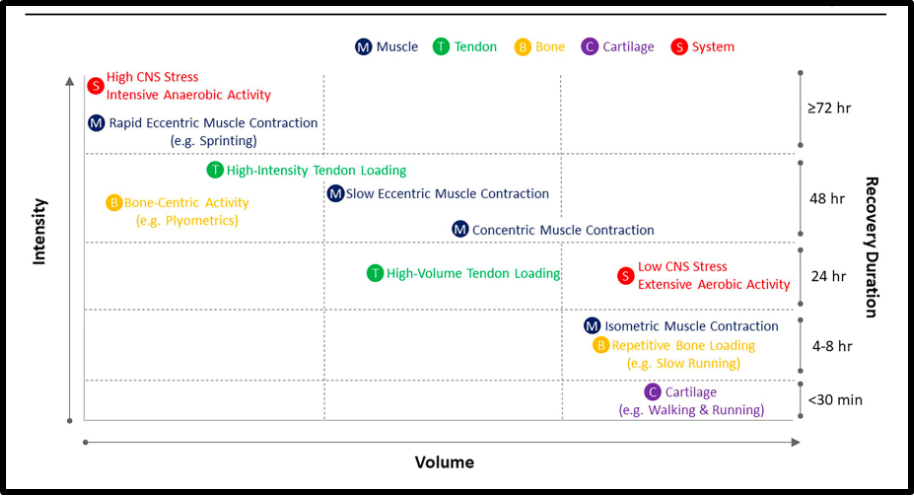

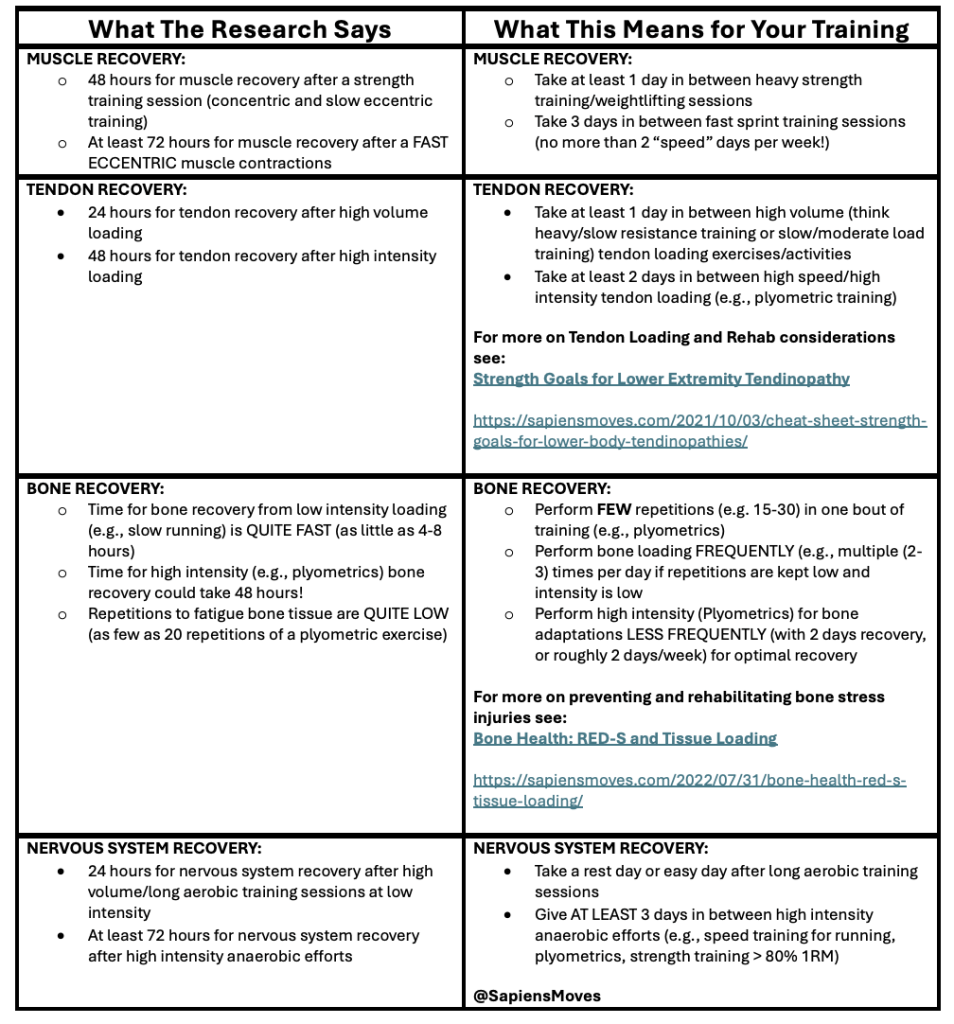

There is a fantastic review paper that came out in 2024 from Dr. Tim Gabbett and colleagues discussing how recovery must be matched to intensity and volume of training and the specific body tissues impacted. See the graphic below from Gabbett, 2024 for a representation of these concepts:

See my chart below for some key takeaways from this research and the figure above that I think are particularly important (and interesting)!

3. Monitor Internal and External Loads and Adjust Accordingly

Physiologically, your body does not really know the difference between having a hard training session in the gym and having a “hard” day at work because your boss yelled at you. As the body interprets it: “Stress is stress,” regardless of what type and form that stress takes.

If you are not creating “Space” between bouts of stress (both internal and external), there is no chance for your body to recover and benefit from training stresses. Recommendations to mitigate stress could include: optimizing sleep, nutrition, hydration, mental and emotional health and social support.

Here are some resources to mitigate and/or minimize “internal stress”:

Free 8-week course on Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (and many resources on meditation including recordings of guided breathe meditation and body scan meditation).

American Academy of Sleep Medicine Free Sleep Resources:

Check out the website above for resources on sleep health including sleep diary, sleep center database, and other information on optimizing sleep!

Circling back to the parallels between creating “Positive Space” for recovery and integrating not only evidence based training strategies but also recovery strategies…and because I think it is beautiful, profound, and resonant; I leave you with this quotation from the Tao Te Ching:

“We join spokes together in a wheel, but it is the center hole that makes the wagon move.

We shape clay into a pot, but it is the emptiness inside that holds whatever we want.

We hammer wood for a house, but it is the inner space that makes it livable.

We work with being, but non-being is what we use.” -Lao Tzu

REFERENCES:

- Brumitt J, Cuddeford T. Current Concepts of Muscle and Tendon Adaptation to Strength and Conditioning. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2015 Nov;10(6):748-59. PMID: 26618057; PMCID: PMC4637912.

- Colquhoun RJ, Gai CM, Aguilar D, et al. Training Volume, Not Frequency, Indicative of Maximal Strength Adaptations to Resistance Training: Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 2018;32(5):1207-1213. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000002414

- Docking SI, Cook J. How do tendons adapt? Going beyond tissue responses to understand positive adaptation and pathology development: A narrative review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2019 Sep 1;19(3):300-310. PMID: 31475937; PMCID: PMC6737558.

- Gabbett TJ, Oetter E. From Tissue to System: What Constitutes an Appropriate Response to Loading? Sports Med. Published online November 11, 2024. doi:10.1007/s40279-024-02126-w

- Mattens F. The Aesthetics of Space: Modern Architecture and Photography. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 2011;69(1):105-114. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6245.2010.01451.x

- Mueller MJ, Maluf KS. Tissue Adaptation to Physical Stress: A Proposed “Physical Stress Theory”to Guide Physical Therapist Practice, Education, and Research. Physcial Therapy. 2002;82(4):383–403.

- Schoenfeld, B.J.; Grgic, J.; Ogborn, D.; Krieger, J.W. Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 3508–3523

- Schoenfeld BJ, Grgic J, Van Every DW, Plotkin DL. Loading Recommendations for Muscle Strength, Hypertrophy, and Local Endurance: A Re-Examination of the Repetition Continuum. Sports (Basel). 2021 Feb 22;9(2):32. doi: 10.3390/sports9020032. PMID: 33671664; PMCID: PMC7927075.